Symbology Of Clocks & Timekeeping in Ancient History, Art & Culture

Author: Clock Shop Date Posted:1 April 2025

Clocks have always been more than just tools for telling time. They hold a deep cultural and symbolic significance, representing everything from power through to the fleeting nature of life and death. Clocks have featured prominently in art and culture throughout history, evolving alongside society's technological advancements, philosophical shifts and movements, which we will explore later in this blog. Clocks and timekeeping have played a key role in art and culture, with their representation largely evolving from the Medieval time through to the modern day. However, the concept of time has been a guiding force for earlier civilisations, far before the invention of mechanical clocks.

Ancient cultures connected the movements of time with their architectural designs, creating structures that aligned with celestial events and the natural rhythms of the universe. Remarkably, many of these structures, built with an understanding of the Universe and celestial movements still stand today.

Timekeeping & Architecture Of Ancient Times

Ancient cultures such as the Egyptians, Mayans, and Mesopotamians demonstrated an extraordinary connection between their architecture and the cosmos, designing monumental structures that aligned with celestial events. These civilisations saw time as not just a linear concept but as a cosmic rhythm that helped their lives. Through their architectural innovations, they created structures that served as earthly representations of the passage of time. Many of these remarkable structures still stand today, providing a lasting testament to their advanced understanding of the concept of time and the universe.

One of the most fascinating examples of ancient timekeeping architecture is Gobekli Tepe, located in modern-day Turkey. Dating back to around 9600 BCE, this site predates written history and may represent one of the earliest known astronomical observatories. The large stone pillars of Gobekli Tepe are arranged in circular formations that appear to align with celestial bodies, suggesting the site was used to track the movement of the stars, the sun, and possibly even the lunar cycles. In essence, Gobekli Tepe acted as an ancient, rudimentary "clock," mapping the celestial rhythms. The fact that this site is so old, long before the advent of agriculture and complex societies, challenges our understanding of early human knowledge of time and suggests that timekeeping was a fundamental aspect of human civilization from its earliest stages.

As agriculture developed during the Neolithic period, societies needed more precise ways to track time. Whilst they didn’t have mechanical clocks, monuments like Stonehenge (around 2500 BCE) were built to align with solar events like solstices, marking crucial times for planting and harvesting crops. Similarly, structures like Newgrange in Ireland and Maeshowe in Scotland were designed to align with the solstices, allowing sunlight to illuminate their interiors during specific key moments of time in the year.

One of the most famous examples of time-representing architecture is the Great Pyramids of Giza. These iconic pyramids, constructed around 2500 BCE, were strategically aligned with the stars, particularly with the star Sirius, which was central to the Egyptian concept of time. The alignment of the pyramids with the cardinal directions—north, south, east, and west—created a massive, earthbound "clock," tracking the sun’s movements through the year. The Egyptians also divided the day into 24 hours (12 for day and 12 for night), a system that laid the foundation for modern timekeeping. They also used devices such as the Sundial to track the hours of daylight, reflecting their sophisticated understanding of time and its connection to the Universe at large. The sundial used the shadow of a stick (called a gnomon) to indicate the time of day based on the position of the sun. The sundial also symbolised the eternal cycles of life and death.

Similarly, the Mayans, with their profound knowledge of astronomy, constructed cities and monuments that functioned as both timekeeping devices and astronomical observatories. El Caracol at Chichen Itza is believed to have been an observatory aligned with the movements of Venus, a key celestial body in Mayan culture. The Mayans had an intricate understanding of time, represented through their solar and lunar calendars, and their architecture mirrored this. The Mayan calendar was one of the most sophisticated timekeeping systems of the ancient world. Mayan structures such as the ones in Copán and Tikal were designed to track the motions of the sun and stars, with alignments that corresponded to specific celestial events, such as the zenith or the solstices.

In Mesopotamia, the ziggurats were symbolic representations of time, acting as both religious centers and astronomical observatories. The Ziggurat at Ur was aligned with the lunar cycles. These towering stepped pyramids were designed to reflect the natural cycles of the moon and the stars, effectively serving as colossal clocks that marked the movement of time.

These ancient structures, functioning as monumental timepieces, continue to stand as awe-inspiring symbols of human ingenuity and a deep understanding of time. Their alignment with celestial events demonstrates how ancient civilizations saw their architecture as a way to embody and track the passage of time, turning their buildings into living clocks that reflected the movements of the universe. As societies evolved, so did their understanding of time, laying the groundwork for the more refined clocks and timepieces that would appear in later periods.

Time In Middle Ages

During the Medieval period, timekeeping underwent significant transformation, although it was still considered far from precise. The concept of time in this period was often tied to religion, with monasteries and churches playing a key role in regulating daily life. Monastic communities used bells to signal the canonical hours for prayer, which became the rhythm of the day. Early mechanical clocks began appearing in the 13th century, primarily in church towers, where they served not only to keep time but also to signal the community for prayer or work. These early clocks were often large rudimentary devices, driven by weights and gears, and were more concerned with marking intervals rather than with precise measurement. The symbolism of time during the Medieval period was intertwined with Christian beliefs about the passage of life. As such, clocks were seen as a reminder of the eternal nature of God and the temporary existence of mankind.

While many original medieval clock mechanisms no longer exist due to age, wear, and/or replacement with newer technology, there are a few existing examples of medieval clock structures that have survived to this day. These include

-The Salisbury Cathedral Clock (England): This is one of the oldest working clocks in the world, dating back to 1386. It's a fascinating example of early mechanical clock technology, albeit it completely lacking a dial and using only a bell to strike the hours.

-Wells Cathedral Clock (England): This is an astronomical clock in Wells Cathedral, dating back to the late 14th century. This clock not only tells the time but also displays the movement of the sun and moon across the sky.

These surviving clocks, along with historical records and fragments of other similarly aged clocks, provide valuable insights into the development of timekeeping technology during the Middle Ages. They showcase the remarkable skills of medieval craftsmen and their key understanding of time, mechanics and astronomy.

Horologium Sapientiae (1450)

.jpg)

Image: Wikipedia

In this Illustration, the clock of wisdom is featured. This derives from Horologium Sapientiae which was written by Henry Suso between 1328 and 1330. In Horologium Sapientiae, the concept of time is portrayed as both a divine order and a moral measure of human existence. Time is seen as a creation of God, structuring both the natural world and human life, with the clock symbolising the passage of time and also to reflect on the use of time for wisdom and virtue.

Horologium Sapientiae (1455)

.jpg)

This image is from a manuscript housed in the Royal Library of Brussels, dating back to the mid-15th century, a recreation of the earlier book Horologium Sapientiae. This illumination depicts "Sapience" and his "Disciple" surrounded by a variety of clocks and astronomical instruments. It offers a great resource for clock historians, as it provides a visual representation of the clocks from that era. The image features a weight-driven clock on the left which is connected to a bell, with the dial displaying two sets of numbers from I to XII, a numbering system used prior to 1450. It also shows an astrolabe, exaggerated in size for clarity, a shepherd's dial/watch, and a table clock alongside other instruments. These instruments offer important insights into the technological and scientific advancements of the time.

Louis de Bruges in front of an astronomical clock Henri Suso- Horloge de Sapience (1470-1480)

.jpg)

Source: Wikipedia

This medieval artwork portrays the courtier and bibliophile Louis de Gruuthuse helping to fix an astronomical clock. These clocks reflected the growing interest in astronomy and the scientific understanding of the cosmos. They also had symbolic value, representing order and harmony of the universe.

“Temperance adjusting a mechanical clock” - L’Épître d’Othéa- Christine de Pisan (1450)

.jpg)

Source: www.europeana.eu

In "L’Épître d’Othéa" written by Christine de Pisan in 1450, temperance and clocks are connected through the idea of balance and self-control. Temperance is symbolised by the steady, regulated passage of time in clocks. The clock also serves as a reminder of life's transience, emphasising the need to use time wisely and avoid excess and greed. In this way, time and temperance are linked through the notion of living thoughtfully and using time in a sensible way.

Another two images from the same timeframe that depict temperance include:

Temperantia with a clock, bridle, spectacles and windmill - Bodleian Library (1450)

.jpg)

Theological and Cardinal Virtues- Ethics Politics and Economics by Aristotle (Image produced in 1400s)

.jpg)

Image Source: Art.com

The Renaissance and Baroque Eras

During the Renaissance Period from the 14th - 17th centuries, clocks began to also take on significant symbolic roles in art, often portrayed to represent the passage of time and the shortness of life. Artists of this era often embraced themes of mortality with the use of timepieces, particularly in the form of memento mori, which were objects such as hourglasses, skulls and clocks, designed with a purpose to remind viewers of their own inevitable death. This period also saw the rise of still-life paintings, where clocks were frequently included to symbolise wealth and power.

Here are a few examples of Renaissance paintings that feature clocks:

"Portrait of an African Woman holding a clock"- Annibale Carracci (1583-1585)

.jpg)

Source: Wikipedia

The clock in "Portrait of an African Woman Holding a Clock" serves as a powerful symbol of time. Its meaning can vary depending on the context and intent of the artist, but it generally is believed to represent themes including the passage of time and social identity.

"The Allegory of Vanity"- Antonio de Pereda (1632-1636)

.jpg)

Source: Image source: Wikipedia

Antonio de Peredas painting includes a clock, an hourglass, old photographs, a blown out candle, skulls and a globe- all objects which are strongly indicative of the passage of time.

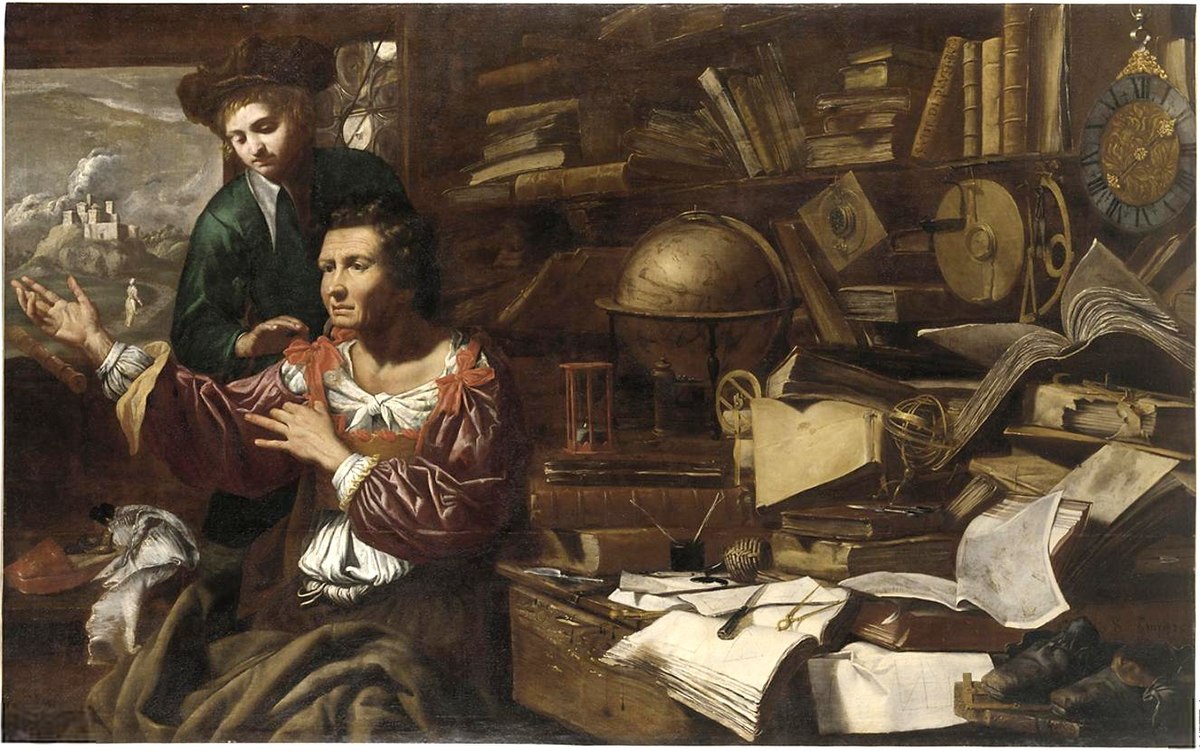

“Euclid of Megara Dressing as a Woman to Hear Socrates Teach in Athens”- Domenico Maroli (1655)

Source: Wikipedia

This artwork is thought to offer a humorous take on an incident from ancient Greek philosophy, where Euclid of Megara, a student of Socrates, supposedly disguised himself as a woman to attend a lecture by Socrates, likely because of restrictions on men being present in certain spaces. The addition of a clock in the painting is symbolic, as clocks were not invented for another 1000 years after this era. Whilst the meaning is not certain, it is believed that the clock could represent the idea that this philosophical moment is rooted in the ancient past, emphasising how philosophy spans generations, and is as relevant in the present as it was in ancient Greece.

In a number of mid-sixteenth-century portraits, the pairing of clocks and skulls became a prominent motif reflecting vanitas themes, which emphasised the transience of life and the inevitability of death. The clock symbolised the passage of time, whilst the skull represented mortality. This combination was particularly prevalent during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, when the contemplation of mortality was central to philosophical, religious, and artistic discussions.

A number of paintings from this era feature this symbology:

Cornelis Visscher the Elder- Jacques Wittewronghele (1574) (left)

Portrait by Jacob Wittewronghele (c.1590–1600) (middle)

Portrait by John Isham (1567) (right)

Images sourced from University of Cambridge

Clocks and watches from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were not only tools for measuring time and regulating daily life, but also common symbols of status and displays of wealth, as evident through the images below:

Portrait by William Chester (c.1560) (left)

Portrait of Anne Fettiplace by Mrs Henry Jones (1614) (middle)

Portrait of a Girl of the Morgan Family- Unknown Artist (1620) (right)

Images sourced from University of Cambridge

The image on the right above, shows the girl holding a small watch in her hand, which is depicted closer below:

Octagonal gilt-brass and silver cased verge watch with date indicator (c.1615–20)

The "verge escapement" was the earliest type of escapement used in mechanical clocks and watches. It dates back to the 13th century and was the standard technology for timekeeping devices for several centuries, often in the forms of verge watches.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, spanning the 18th and 19th centuries, introduced significant innovations in clockmaking. Advances in mechanical precision allowed clocks to become more accurate and accessible. As urbanisation surged, public clocks in town squares became a fixture. This era also marked the start of new artistic movements such as Art Nouveau, where clocks were designed not only for function but also as decorative art. Artwork depicting clocks continued on throughout the 18th century, as the timeframe witnessed significant growth in science, industry, and culture. This Age of Enlightenment fostered intellectual advancement, the Industrial Revolution along with the expansion of global trade and exploration, leading to greater cultural exchange and the development of new ideas. During this time clocks were less depicted in artwork but became a prominent physical household staple, particularly in wealthy households.

“Four Times of the Day: Noon” - William Hogarth (1736)

Source: Wikipedia

In this particular painting from the four part series, the clock is central to Hogarth’s work. The time depicted is noon, which marks the midpoint of the day. The depiction of time in this context can be a reflection on how daily life is structured, the consequences of the passing hours, and the need to be mindful of how one spends it.

The 20th Century and Modern Design

By the 20th century, clocks began to lose much of their ornate, decorative qualities, embracing a more minimalist aesthetic. As clocks became functional objects, they also became cheaper, and were integrated into home decor as a staple, seen as central elements in the design of living spaces.

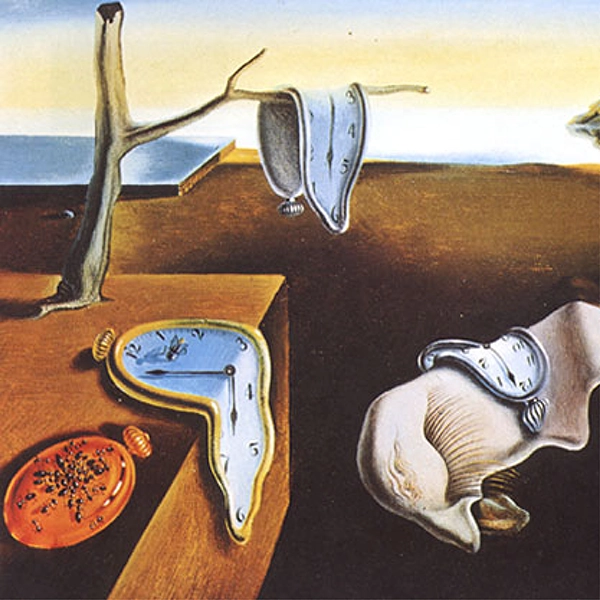

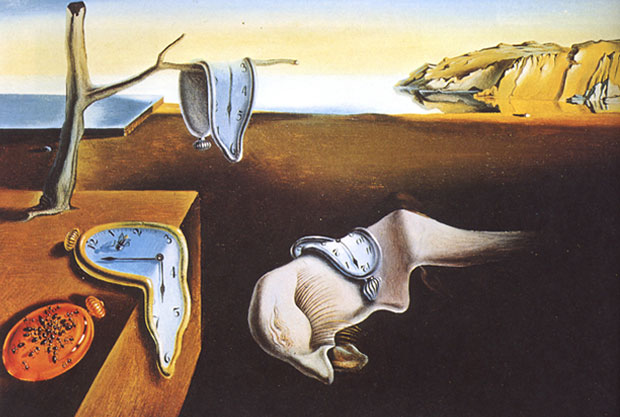

At the same time, the surrealist movement brought clocks back into art in unexpected ways. Salvador Dali's The Persistence of Memory is perhaps the most famous example of clocks used symbolically from this timeframe. The Persistence of Memory artwork challenges the conventional understanding of time, making the viewer question its fluidity and subjective nature.

“The Persistence of Memory” - Salvador Dali (1931)

Image Source: Wikipedia

The Bauhaus movement which emerged in the early 20th century, was instrumental in modern design, offering an emphasis on functionality, simplicity, and the integration of art and technology. Bauhaus designers approached clocks not just as timekeeping devices but as works of art, blending aesthetics with practicality. Bauhaus clocks became a platform for innovative design, with clean lines, geometric shapes, and industrial materials taking center stage. These modern designs were in stark contrast to the ornate, decorative clocks of previous eras, reflecting the movement's emphasis on modernity and the idea that design should serve both form and function.

Image Source: Clock Shop

Similarly, George Nelson, who was a key figure in American modernism embraced this philosophy in his own approach to clock design. Nelson created clocks that were both functional and artistic, often using bold, unconventional materials like wood, metal, and plastic. His "Sunburst Clock" from the late 1940s features radiant, symmetrical spokes and minimalist aesthetics, transforming the clock from a mere tool into a striking decorative object. Similar starburst style clocks became particularly popular in the 1950s and 1960s, during the height of mid-century modern design, and are experiencing a new dawn of popularity in the modern day. These clocks were a prominent feature of the mid-century modern aesthetic, which emphasised clean lines, geometric shapes, and bold, innovative designs.

Image source: Clock Shop

Both the Bauhaus and Nelson's works, along with Andy Warhol decades later, reflect a modern approach to clocks, where the boundaries between utility, design, and art were intentionally blurred, paving the way for the way we view everyday objects in contemporary design. As the 20th century progressed, clocks appeared not only in art, but also in pop culture, music, and advertisements, becoming symbols of modern life’s fast pace and ever-changing nature.

Contemporary Clock Design

In the modern era, clocks continue to evolve in response to changing technologies and tastes. The rise of digital clocks, smartwatches, and other high-tech timepieces has led to new forms of clock design, where function is favoured to look. However, there are still many designers who view clocks as an artistic medium, creating pieces that blend cutting-edge materials and technology with timeless principles of design. Some famous examples of clocks used in art from this timeframe include:

Untitled" (Perfect Lovers)- Félix González-Torres (1987-1990)

Untitled (Perfect Lovers), has been featured in many exhibitions worldwide, and represents the theme of separate mortality in lovers. The piece consists of two visually identical clocks, initially synchronised but gradually falling out of sync over time. Torres explains the piece, quoting, “Don’t be afraid of the clocks, they are our time… We conquered fate by meeting at a certain time in a certain space. We are a product of time, therefore we give back credit where it is due: time. We are synchronized, now, forever. I love you.”

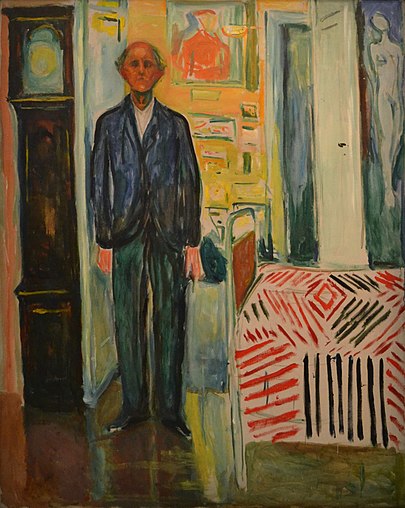

Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed- Edvard Munch (1940-1943)

Image source: Wikipedia

Between the Clock and the Bed reintroduces Renaissance themes of clocks and mortality as the artist explores his personal confrontation with mortality and existential anxiety. In this piece, Munch places himself between a clock and a bed, two powerful symbols of life and death. The clock represents the passage of time, whilst the bed, often associated with rest and sleep, here functions as a symbol of the final rest. Munch's self-portrait in this context reflects his anxiety and introspection about his own existence and the ticking of time.

Conclusion

From their symbolic representations in Renaissance art to their role in modern, minimalist design, clocks have held a special place in human culture for centuries. The exploration of clocks and timekeeping throughout history reveals the cultural, philosophical, and artistic significance of time in human society. From ancient civilisations that used monumental structures to align with celestial events, to the intricate clockwork designs of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, clocks have consistently served as both functional tools and powerful symbols of mortality, power, and wisdom. As time evolved, so did the representation of clocks in art and culture, from their role in religion and philosophy of the Medieval times through to their modern simplistic design in the 20th century. Clocks have not only shaped our understanding of time but have also reflected our ever-changing relationship with it, from large physical structures to intricate mechanical marvels, through to minimalist, art-inspired pieces and themes of mortality and the fleeting nature of life itself. As time continues on, clocks will continue to connect the worlds of practicality, art, design, and human experience all in one. The representation of clocks in both art and architecture tell a story of how humans have always sought to understand and express the passage of time, linking the past, present, and future through the lens of creativity.